The Marlborough area has a very rich shore-based whaling history.

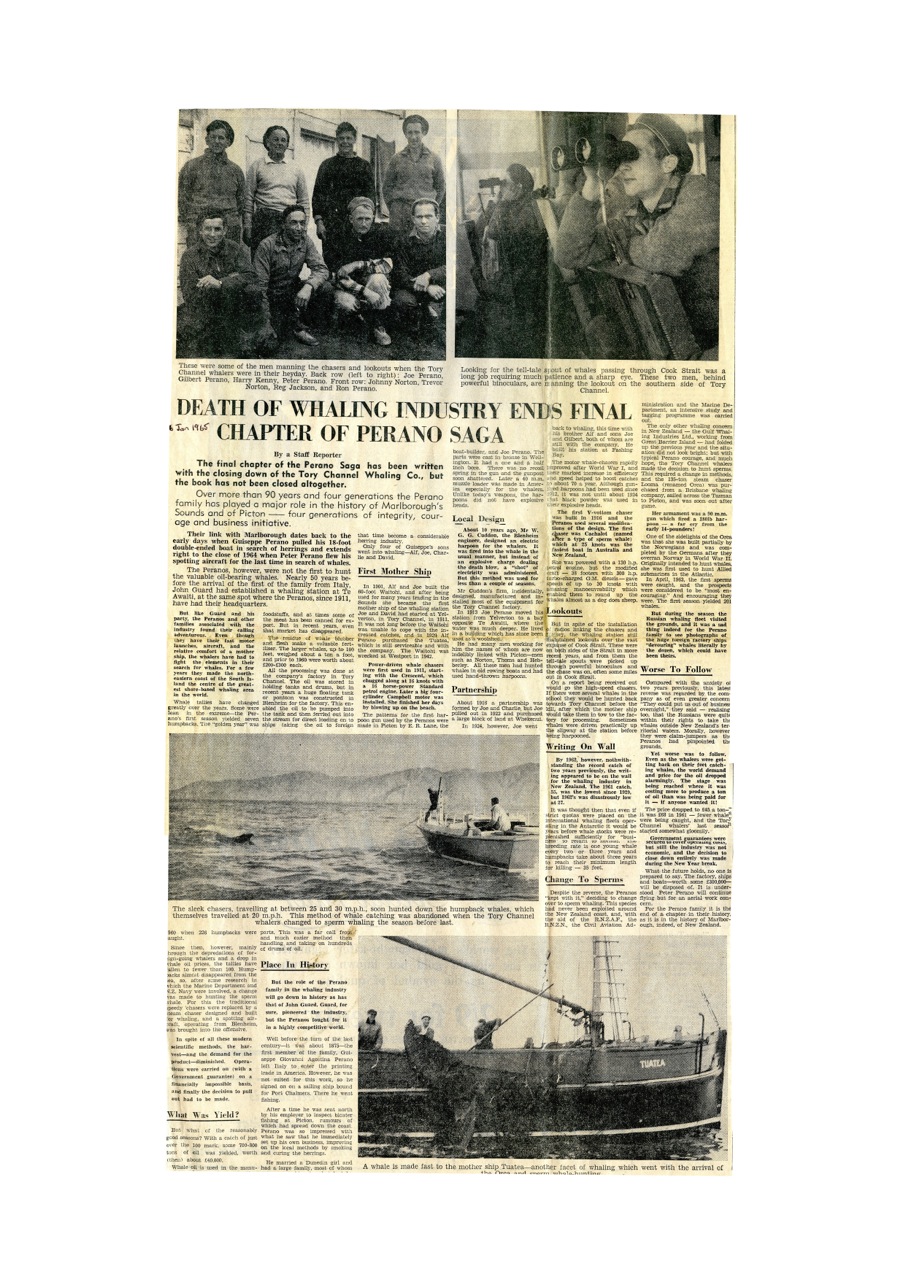

For a century or more Picton serviced New Zealand’s most intensive shore based whaling industry with the first station established in 1827 by Captain John Guard at Te Awaiti in Tory Channel. The Tory Channel whaling operation established in 1911 by Joseph Perano at various sites was, until the closure in 1964 of the Fishing Bay station, New Zealand’s longest continuously operating whaling operation until it processed its last whale catch on 21 December 1964.

Nearby at Port Underwood there were some six shore stations active in 1836 with some 18 whaling vessels – mostly American, competing for whales.

The archaeology and history of this industry is described in detail in a number of journals and books including The Perano Whalers by Don Grady, the excellent record by Nigel Prickett for the Department of Conservation, The Archaeology of New Zealand Shore Whaling, as well as the numerous other publications by DOC, the classic Don Grady Sealers & Whalers in New Zealand Waters (1986), and the vast list of museum, academic, scientific and popular publications on the subject.

Cetaceans and New Zealand

There are at least 80 species of whales, including dolphins and porpoises (cetaceans) divided into baleen or filterfeeding whales and toothed whales.

The baleen feeders consist of some 13 species ranging in size from the pygmy right whale (6.5 metres) to the blue whale (27 metres).

They include the blue, fin, sei, Bryde’s, 2-3 species of minke, Omura’s whale, humpback, bowhead, northern and southern right whale, and pygmy right whale.

Of the above the right whale, minke and Bryde’s and Pygmy right whale all breed in New Zealand waters.

The majority of cetaceans are toothed and there are some 69-73 species including the sperm whales, beluga and narwhal, 21 species of beaked whales and 34 species of dolphins and 6 species of porpoises. The sperm, killer whale and pilot whales are often seen in New Zealand waters.

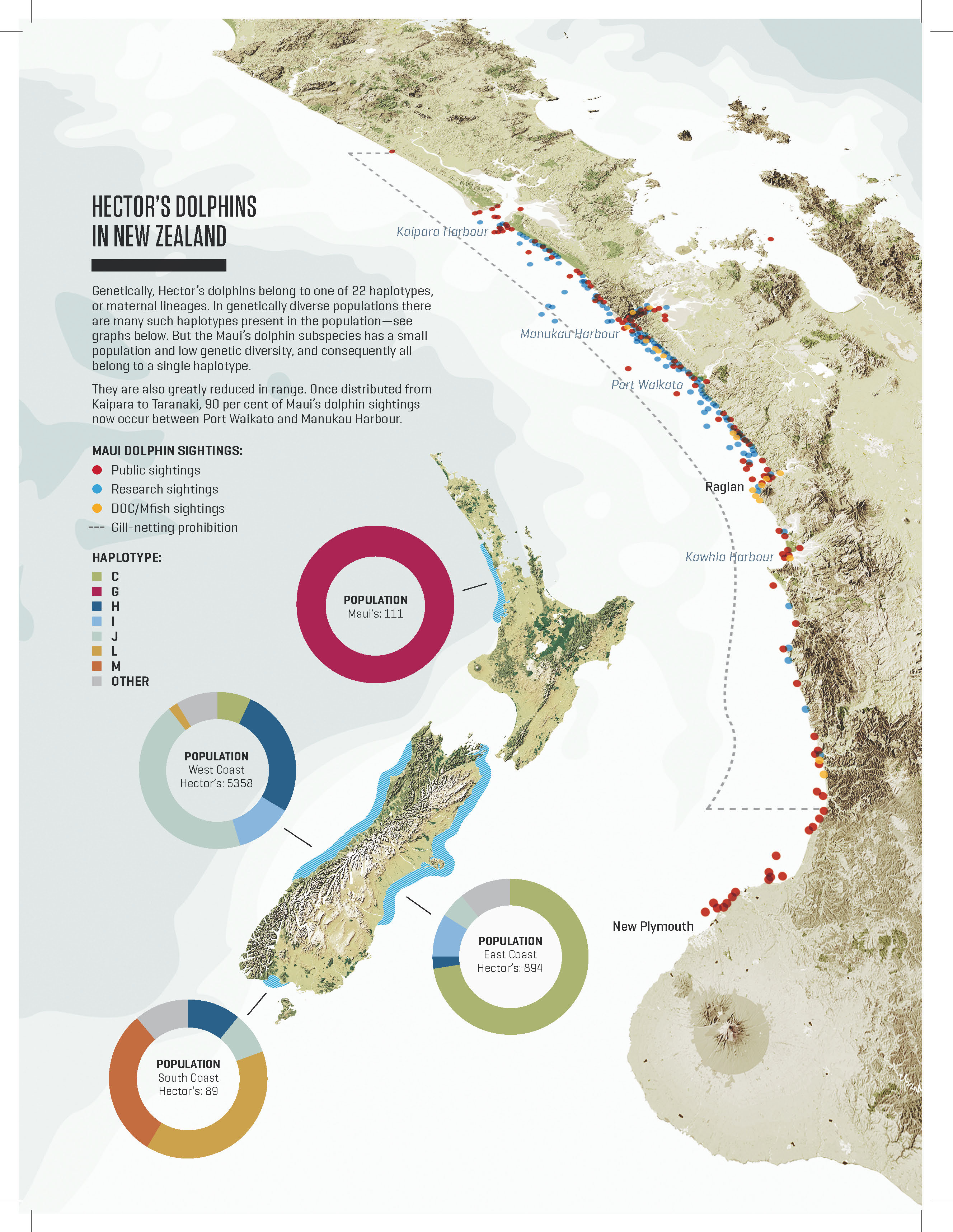

Nearly half of the world’s whale species are seen around New Zealand’s coasts with 9 species of baleen whale, 33 species of toothed whales including 3 sperm whales, 13 beaked whales, 16 dolphins and 1 porpoise. Among the dolphins are the native and seriously threatened Hector’s dolphin (which includes the North island sub-species Maui’s dolphin).

Māori, whales and whaling

The history of the whaling industry is also deeply intertwined with Māori history.

Tribal knowledge of whales

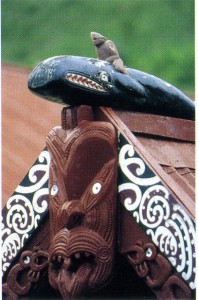

Māori have a long association with whales. While whales provided food and utensils, they also feature in tribal traditions and were sometimes guardians on the ancestors’ canoe journeys to Aotearoa. Oral histories recall interactions between people and whales in tribal stories, carvings, specialised language and place names. There is also a wealth of tribal knowledge about whales.

Māori have a long association with whales. While whales provided food and utensils, they also feature in tribal traditions and were sometimes guardians on the ancestors’ canoe journeys to Aotearoa. Oral histories recall interactions between people and whales in tribal stories, carvings, specialised language and place names. There is also a wealth of tribal knowledge about whales.

Whale names

Names for the different species of whales vary from tribe to tribe. One of the old terms for whales was ‘ika moana’ – fish of the sea. They were part of the family known as ‘te whānau puha’ – the family of animals that expel air. While ‘tohorā’ (or tohoraha) is considered an all-embracing term for whales, it also refers to the southern right whale.

Whale Origins

There are many tribal versions of the origin of whales. Some say Tangaroa (god of the sea) is the ancestor of sea creatures, while others name Te Pūwhakahara, Takaaho and Tinirau as progenitors of whales. Another tradition cites Te Hāpuku as the main ancestor of whales, dolphins and seals as well as tree ferns, which are often known as ‘ngā ika ō te ngahere’ – the fish of the forest.

There are many tribal versions of the origin of whales. Some say Tangaroa (god of the sea) is the ancestor of sea creatures, while others name Te Pūwhakahara, Takaaho and Tinirau as progenitors of whales. Another tradition cites Te Hāpuku as the main ancestor of whales, dolphins and seals as well as tree ferns, which are often known as ‘ngā ika ō te ngahere’ – the fish of the forest.

Whales have an important place in Māori tradition. Several tribes tell of the arrival of their ancestor, Paikea, on the back of a whale. Although there is debate as to whether Māori hunted whales, it is clear they regarded stranded whales as a valuable source of meat, and used whale teeth and bones for ornaments.

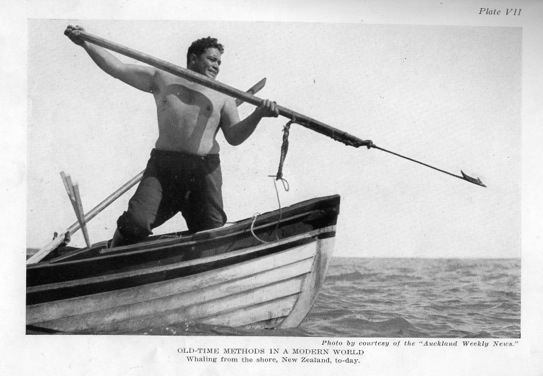

Ship-based whaling

Māori men were eager recruits for whaling ships, as replacements for crew who had deserted; whaling was exciting and an opportunity to see the world. As early as 1804 a Māori was reported on board a whaler. In 1826, British whaleboat owners reported that one vessel had 12 Māori crew, who had proved ‘orderly and powerful seamen’. At a gala day in Hobart in 1838, 30 Māori – one-third of the whalers present – took part in whaleboat races. Māori quickly introduced these boats at home, and by the 1840s whaleboats were widely used by Māori in New Zealand.

Visiting whalers also had a profound impact on Māori society. Especially in the Bay of Islands, whalers’ demands for potatoes and pork provided an early trade opportunity for Māori. In return, whalers often supplied muskets and alcohol, while their liaisons with Māori women further disrupted Māori society. On the positive side, it is said that the modern kūmara entered Māori horticulture as an American whaler’s sweet potato.

Shore-based whaling

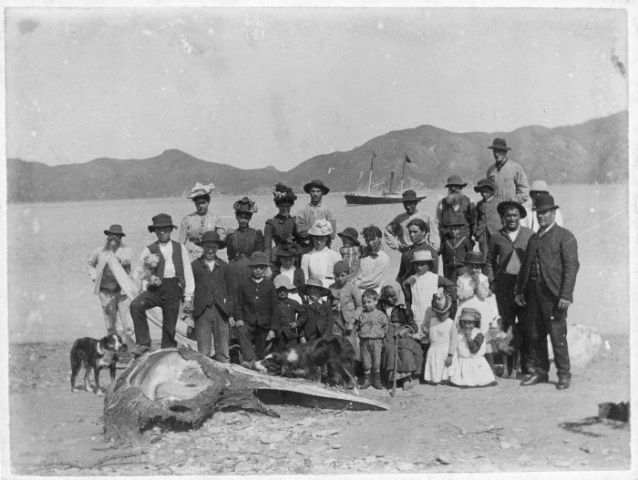

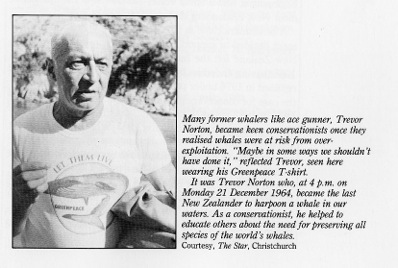

Shore whalers also depended on Māori for food and women. Many early whalers such as Dicky Barrett, Phillip Tapsell , Jacky Love and the “original” Heberley, James Heberley married into Māori families. Māori men became important whalers at shore stations, comprising 40-50% of the shore whalers. Many of those Māori whalers connected to the shore based stations in the Sounds such as the Nortons and Huntleys still reside in the Marlborough area and form an important part, like the Heberleys of New Zealand’s commercial whaling history.

Māori and whales today

Today, the Māori ethos toward whales is gaining strength as young Māori are becoming more aware of their relationship with the marine environment. Large-scale commercial whaling may be a thing of the past and certainly the Māori of today do not generally support a resumption of this practice. Nevertheless, they have expressed support for other indigenous people around the world who have similar legal and or cultural and traditional rights to sustainably harvest whales to satisfy their own needs. Equally, there is a strong move by Māori in New Zealand to convince government to recognise their right, enshrined in the Treaty of Waitangi, to collect meat from stranded whales for human consumption. In this we see a continuum back to the respectful Paikea philosophy concerning whales as a resource to be carefully utilised, in the Tinirau tradition.

To download Martin Cawthorn’s excellent article on Māori, Whales and Whaling click here.